This article was worth re-posting from the folks at

EasternSlopes.com (the Web’s leading destination for outdoor enthusiasts who love mountains of the Eastern U.S. and Canada.).

Written by: The Editors of EasternSlopes.com on September 27, 2012

October through May here in the northeast can be tough on paddlers:

ice, wind, and cold can make you dream of warmer times and open water.

But October and November are lovely months for paddling; so are April

and May. January, February and March typically offer the fewest paddling

opportunities; December and March are typically transition months when

you might be able to get some paddling–or not. But even in the dark of

December or the dead of winter, you occasionally get those lovely days

when the sun is shining, the wind is gentle and the air is warm: perfect

days for paddling—if you can find some open water to paddle on.

There’s a catch, however. No matter how bright and strong the sun is,

however warm the air is, the water you are paddling on is is cold,

cold, cold . . . too cold for safety if you aren’t properly prepared.

Cold water and human beings just don’t mix very well. That’s true

whether you are talking about a 33-degree rainstorm while you are

backcountry skiing in January or falling into a 45-degree river in

November or April. The danger, of course is

hypothermia, the inability of the body to maintain its core temperature.

We haven’t been able to track down the original source (both have been attributed to the

Coast Guard Auxiliary,

but we haven’t been able to verify that), but we’ve heard two different

versions of the so-called 50-50 rule of how rapidly hypothermia can

affect you in cold water. Verified or not, both are worth serious

consideration before you leave shore when the water is cold.

One of the 50-50 rules states that without protective clothing and a

PFD, you only have a 50-50 chance of being able to swim 50 yards in

50-degree water. It depends a lot on the swimmer’s body composition,

physical condition and age, but it certainly helps explain why people

often drown very close to shore in cold water.

The other 50-50 rule is that a 50-year-old person has a 50-50 chance of surviving 50 minutes in 50 degree water.

|

| Not

all cold water paddling is in a kayak or canoe. Here it’s big water on

the Kennebec River and the rafters are dressed for comfort with wetsuits

beneath wind-proof dry tops. (Tim Jones photo) |

What Is “Cold”

The safety experts at the

American Canoe Association recommend

wearing protective clothing (a wet or dry suit) when both the water

temperature and the air temperature are below 60°F., when you will be

more than 1/4 mile from shore and the water temperature is below 60°F.,

(no matter what the air temperature is), and if you expect be repeatedly

exposed to cool (65-70°F or less) water in cool or mild weather.

One thing to remember, however is that the colder the water and the

colder the air, the greater the danger and the more rapidly heat loss

can affect you. Fishermen often carry a

thermometer to determine the water temperature. That’s not a bad idea for paddlers, either. If you are paddling on the ocean,

National Oceanographic Data Center keeps track of Coastal Sea Temperatures around the country.

But it’s really simpler than that: if it feels cold, it probably is cold–and you should be prepared.

Cold, Hard Facts

The best information we’ve found on the web about hypothermia from cold water immersion is a Canadian website called

Cold Water Boot Camp. According to that site, in 2004, 130 boaters drowned in Canada, 60 percent in water under 50 degrees F.

What’s scary is, of those drowning victims:

Only 12 percent were properly wearing a PFD,

43 percent were less than seven feet from safety

66 percent were less than 50 feet from safety.

The Cold Water Boot Camp documents a controlled experiment directed

by Dr. Gordon Giesbrecht (known as “Professor Popsicle”). Volunteers

jumped into very cold water and attempted to save themselves (DO NOT try

this at home!). It’s important to realize that this was a controlled

experiment. These volunteers: 1) knew they were going to go into the

water and 2) were surrounded by people and equipment to save them if

they got into trouble. This very likely helped them avoid the panic most

of us would feel if we suddenly and unexpectedly flipped a canoe, kayak

or whitewater raft. The videos of these voluntary immersions (click on “

Boot Campers”) are absolutely fascinating. Okay, they are downright scary. We’d strongly recommend watching some of them—

especially if you are a strong swimmer and are not the least bit afraid of a little cold water.

Dr. Giesbrecht has coined the concept of “

1-10-1”

to describe the first three stages of human reaction to cold water

immersion (you can actually watch it happening in the videos) and the

approximate time each stage takes.

Stage 1 is your initial reaction to a plunge into cold water. This is

called “Cold Shock,” and it lasts about 1 minute. If you don’t have a

life jacket on to help you stay afloat, you can drown that quickly. One

of the things that happens when you hit cold water is that you

immediately gasp for air. It’s a reflex, probably uncontrollable. If

your face happens to be underwater when you gasp . . .Let’s repeat that:

if you are suddenly plunged into cold water without a good PFD,

you can drown in one minute or less.

Stage 2, which takes about 10 minutes (or less) is “Cold

Incapacitation.” Even strong swimmers lose the ability to move

themselves through the water effectively. And, worse yet, cold affects

judgement. In the videos, some subjects who could still swim, swam

directly away from shore and safety. Again, without a life vest, you

will likely

drown in 10 minutes or less . . .

Stage 3 is unconsciousness due to hypothermia. Think about that scene from the movie

Titanic when

the dawn after the accident reveals all those cold, dead people

floating in their life jackets. According to Dr. Giesbrecht, it takes

about an hour for most people to lose consciousness. Assuming you don’t

drown, how long you live after losing consciousness depends largely on

your body mass index and gender. Here’s one place where short and fat is

where it’s at for survival. There’s a

chart on the 1-10-1 page

which shows this clearly. It doesn’t account for how you are dressed.

You are going to live a lot longer in a wetsuit and even longer in a

good dry suit with insulation layers underneath.

|

| You

know you are going to get wet learning to roll a kayak, Be prepared if

the water’s cold. It certainly was when this photo was taken! (Tim Jones

photo) |

If you are looking for still more info, the

American Canoe Association has an excellent “

Cold Water Survival” page.

Charles River Canoe and Kayak also has excellent information on

how to dress for cold-water paddling. New England Sea Kayaker published a detailed article by Daniel E. Smith on

Coldwater Paddling Preparation and Outfitting back in 2005 that’s loaded with good information.

There’s also some useful information on the website

University of Sea Kayaking,

but it isn’t well organized or easy to locate. Click on [Library] in

the left-hand nav bar, then [environment], then [exposure] to find a

good hypothermia chart and some tips for dressing for cold-water

exposure. Our thanks to loyal reader “Van” for digging this out and

sending instructions on how to find this material.

|

| Preparing

to paddle on a frosty morning . . .but warm and comfy in a dry suit

that will keep you safe if something bad happens on cold, cold water.

(David Shedd photo) |

Rules To Live By

No matter what the air temperature is, if the water is much below 60

degrees, you need to consider the possible consequences of prolonged

immersion, and if it’s below 50, you really need to make safety a

priority and prepare for the worst.

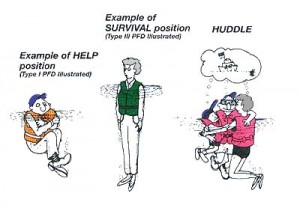

1) Know your own ability levels, both for paddling skills and rescue

techniques. Know what to do if you end up in the water, including the “

HELP”

(Heat Escape Lessening Position). Knowing how to do an “Eskimo Roll,”

to roll a kayak back upright if you’ve flipped, is a really good safety

skill for cold water kayak paddling (and fun to learn).

2) Don’t go alone. Have at least one other person along who can help

you if you end up in the water. It’s safest if you both know (and have

practiced) some basic kayak rescue techniques.

3) Have a quality life vest and ALWAYS wear it. This is true every

time you paddle, but is absolutely critical when the water’s cold. If

you go over into cold water without your PFD on, you probably won’t be

able to get it and get it on before the cold incapacitates you. If you

don’t believe us, watch those

Cold Water Boot Camp videos!

4) Dress properly. Best is a full dry suit with layers of synthetic

insulation beneath. Second best is probably a full neoprene wetsuit (or

“Farmer-style” bibs and jacket) which will insulate your core and

extremities. Third is a “Paddling suit” either one piece or separate top

and bottom which won’t keep you perfectly dry but will certainly help

you stay safer. The colder the water, the more protection you need.

5) Don’t take chances. Strong currents, strong winds, traveling far

from shore all increase the danger. Pick your day, pick your place, pick

your companions, and paddle safely.

Cold Water Accessories

|

| There’s

still snow in the woods but the paddling is lovely on a warm, early

April afternoon when most people are just dreaming about summer

watersports. (Tim Jones photo) |

Knowledge and Good Judgment: The number one

accessory you need to keep yourself safe in cold water is between your

ears. Learn rescue techniques, and be able to help both yourself and

your paddling partners. And, most important, know when it’s safe for YOU

to paddle and when it isn’t. With those “accessories” you probably

won’t get into trouble and need the rest of this stuff.

PFD: Since you always wear a PFD when you are

paddling anyway, we don’t need to remind you that it’s especially

critical in cold water. Right? But here’s the place where you want a

paddling-specific PFD in good condition with a little extra flotation.

Before you start shopping for a PFD, check out these

guidelines for choosing a PFD from the Personal Flotation Device Manufacturer’s association.

Kokatat, NRS, Stohlquist, Extrasport, Harmony, Stearns, MTI, North Water and some others all make good ones. Don’t scrimp on your PFD when you are paddling in cold water!

Dry Suits: Okay, let’s be clear right up front. If

you want to be safer and more comfortable while paddling on cold water,

there is nothing better than a quality dry suit. Yes, a dry suit is a

huge investment (they can cost more than a good used kayak). But a

quality drysuit will last for decades if you take good care of it (keep

it clean and dry and store it in a cool, dry, dark place) and it will

get you more paddling days each year. Money well spent.

Tim counts his

Kokatat Gore tex dry suit as one of his all-time favorite pieces of outdoor equipment. He’s had it since 2005 and has used it many times each season for

seakayaking,

white water paddling and early or late season

whitewater rafting. He’s also used it as a safety suit while fishing in northern Quebec and Labrador.

Tim’s dry suit has the front “relief” zipper, a really nice touch (some

women’s models

have drop seats for the same purpose). It originally came with latex

ankle gaskets which were really difficult to get on and off, so, a

couple of years ago he sent it back to Kokatat and for $100 they

replaced the ankle gaskets with the Gore-Tex booties that now come

standard on their newer drysuits. Kokatat’s customer service is first

rate, and the upgrade well worth the money.

Of course Kokatat isn’t the only company making dry suits. NRS, one of the oldest names in the paddling business, makes

dry suits for men and women.

Stohlquist, another well-respected name in paddling gear, also makes three different models of

dry suits for paddlers.

OS Systems offers a variety of dry suit models.

Immersion Research offers it’s “

Double D” rear-entry dry suit with men’s relief zipper.

Palm drysuits were once available in this country for awhile but now seem to be sold only in Europe.

One note of caution about dry suits. Make sure you get one which is

designed specifically for paddling and allows plenty of arm and shoulder

mobility. The heavy-duty neoprene dry suits made for cold water

diving, and the “survival suits” made for search and rescue and

commercial fishing, are generally too restrictive and don’t really work

for paddling.

|

| Spring

whitewater paddling on recently melted snow can be too cold if you

aren’t prepared. This paddler chose pogies rather than gloves for better

paddle control. (Tim Jones photo) |

“Paddling Suits”: It’s best to think of these as

“semi dry” or “mostly dry” suits. They typically have neoprene gaskets

at the neck and wrists which aren’t as watertight as the latex in a dry

suit but are much more comfortable. They are really wonderful if you

don’t need them and far better than nothing if you do. But if you

suddenly find yourself immersed in really cold water, you are probably

going to wish you had a dry suit.

Wet Suits: While not as comfortable as a paddling

suit or a full dry suit, a wet suit is a much more economical way to

extend your paddling into cold-water season. The same cautions apply

about choosing carefully to avoid garments that restrict your paddling

motion. Many of the wet suits designed for scuba diving and even surfing

and water skiing are just too restrictive for paddling. Most paddlers

choose “Farmer John” or “Farmer Jane” styles which leave the arms and

shoulders free yet help insulate your critical core area. When combined

with a good paddling jacket, a Farmer-style wetsuit can provide good

protection from cold water and cold weather. If you sign up for a

commercial

white water rafting trip

when the air and water are cold, this is exactly what they’ll outfit

you with. One caution, though; NEVER use a farmer john without a good

PFD. Neoprene floats, which has advantages, but all of that neoprene on

your legs will float you head-down…if you don’t have your PFD on, that

can kill you faster than the cold water.

Two things to note about wet suits and paddling:

One is that, since they don’t breathe, they aren’t very comfortable

when the air is warm but the water is cold. In other words they

generally work better if you’re wet than if you aren’t, and in paddling

on cold water you are generally better off if you stay dry. Choosing a

thicker wetsuit which works better in colder water just makes the

problem worse. Paddling on cold water on a warm day can get pretty

uncomfortable in a wetsuit.

Second, wetsuits work best in water above 50 degrees, and if you get

wet, then come out of the water into cold air (especially if there’s

wind), a wet suit can get uncomfortably cold very fast.

That said, we often use a shorty wetsuit paddling on the coast of

Maine in the summer and early fall. The water is still too chilly for

safety without some insulation but it’s much too warm for a full

drysuit, and the wetsuit provides that extra edge of protection.

Paddling gloves or “Pogies”: Your hands are the

first thing to get cold and uncomfortable. Neoprene paddling gloves and

“pogies” (over sized neoprene mittens which allow you to hold directly

onto the paddle shaft for control) help keep your hands comfortable and

your fingers functional. Here’s the conundrum: pogies are better for

actual paddling, but useless once you have to let go of your paddle (to

climb back into a capsized boat, for example). Gloves sacrifice some

paddle “feel” but help more if you really need them.

Hats: These can range from a fleece beanie to keep

your ears warm on a chilly morning (and help hold some warmth if you

get wet) to a full neoprene balaclava to wear if you know you are going

to get wet when it’s cold. Just make sure you have a hat with you. If

nothing else, it helps keep your hands and feet warm.

Obviously if you end up in cold water, you are going to try to get

out as soon as possible. But what if you can’t get into your boat or

swim safely to shore.Here’s where your PFD (which you are ALWAYS wearing

properly, right?) and the HELP (Heat Escape Lessening Position) can

keep you alive. In the HELP posture you cross your arms tightly against

your chest and draw your knees up. Remain calm and still. Unless you

have something you CAN swim to, do not try to swim. Unnecessary movement

will use energy that your body requires to survive. The more still and

huddled you stay, the longer you live.

Why We Go: An Early Season Kayak Camping Adventure On The Connecticut River (Mostly Dry and Mostly Warm!)

Just as you don’t let “bad” weather keep you prisoner in winter, you

don’t let cold water keep you from paddling in the spring and fall. You

prepare for it with the proper equipment and make smart choices, build a

safety margin into your plans and then go and have fun.

In early April, two of us, EasternSlopes.com’s senior editor David

Shedd and executive editor Tim Jones, wanted to paddle to a private

river island, to clean up around a campsite we maintain there. We use

this island all summer long for

overnight getaways and

gear testing.

The day we’d originally planned was just too cold, windy and rainy, so

we waited for better weather. Mother Nature is always in charge . . .

|

| The

air is chilly, the water is downright cold, but it’s a beautiful

morning for paddling if you take safety into consideration. (David Shedd

photo) |

Finally, the proper weather arrived, warm, sunny, not too breezy, and

we loaded the kayaks with camping gear (all in dry bags) and tools. We

were dressed to allow ourselves the best chance to survive if we

suddenly found ourselves swimming in the 40-degree water. Tim was

wearing the one-piece Gore-tex Kokatat dry suit he’s used for many

years, with a layer of warm, dry fleece underneath. On this trip, David

was wearing a neoprene “Farmer John” wetsuit with a paddling jacket and

pants over it. (He’s since purchased a two-piece Kokatat dry top and dry

pants outfit.)

We donned our PFDs, launched, and paddled the mile and a

half to the island in the chilly sunshine. The wind was steady but at

our backs and didn’t really affect us. We made it to the island and

landed without incident (which was how it was supposed to go!), only

getting our feet wet as we beached the boats at the campsite.

Sometimes, there’s no way to avoid wet feet and this was one.

We had a wonderful afternoon cleaning up the campsite and relaxing in

the warm April sunshine, eating a great dinner (you can carry a lot of

food in a kayak), solving the world’s problems, and spent a comfortable

night tucked in our sleeping bags with everything we needed to

stay warm as the nighttime temperature plummeted.

The next morning it was flat out COLD, but we needed to get going

early to make a planned breakfast meeting. Also, we had to paddle

upstream back to our cars and, on this stretch of dam-controlled river,

the currents build with the day as dams above and below release water to

generate electricity. Paddling back upstream is MUCH easier in the

early morning. We rolled out of our sleeping bags and began making

coffee/tea while it was still dark (and COLD!). We had camp pulled down

and packed in the kayaks before the sun showed completely over the

horizon. Did we mention it was COLD?!? Temps were in the mid 20s, not

uncommon for an April morning in northern New England. Our water shoes,

wet from the landing the day before, were frozen solid and very hard to

zip with cold fingers. And, frankly, David really didn’t enjoy having to

pull on a COLD neoprene wet suit that COLD morning. For Tim, donning a

drysuit over cozy fleece was much more pleasant.

There was another benefit to our early start, however. The river in

the early morning light was simply gorgeous, with wispy coils of mist

lifting off the water which was now much warmer than the air (if it

hadn’t been, we could have walked home on it!). The wind was calm and

the sun growing stronger as we paddled against a mild current back to

the cars. The hats, gloves and exercise kept us warm enough for comfort

(except for David’s wet feet ).

Neither one of us got anything more than our feet wet on our whole

adventure and that only when landing and launching. But that little bit

was enough to remind us how COLD the water can be when you are paddling

early or late in the season. We were well dressed for safety and

prepared for the cold water should we have found ourselves swimming.

Being prepared allowed us to get out on, not one, but two perfect

paddling days in early April, with a whole season of paddling ahead.

If you paddle two days in a row your drysuit will be dry the next day....or even later that same day.

If you paddle two days in a row your drysuit will be dry the next day....or even later that same day. My

suit of choice for day paddles or short fitness paddles is the Kokatat

Lightweight Goretex Suit. This suit is the lightest weight and most

breathable suit in the Kokatat line. It features Gore-tex socks which is

a must have. They keep your feet warm and dry and allow you to wear

whatever socks you want underneath. This suit also has a neoprene neck

which isn't fully waterproof but is much more comfortable to paddle in

and will still keep most water out as long as your not spending long

periods of time with your head under.

My

suit of choice for day paddles or short fitness paddles is the Kokatat

Lightweight Goretex Suit. This suit is the lightest weight and most

breathable suit in the Kokatat line. It features Gore-tex socks which is

a must have. They keep your feet warm and dry and allow you to wear

whatever socks you want underneath. This suit also has a neoprene neck

which isn't fully waterproof but is much more comfortable to paddle in

and will still keep most water out as long as your not spending long

periods of time with your head under. My

suit of choice for bad weather and expedition paddling is the Kokatat

Expedition Suit. This suit has it all. Pockets, socks, durable exterior

and a hood. Kokatat is also the first company to allow online

personalization and customization of your suit. Check out the website

and play around with the GIZMO customizer. This allows you to custom

tailor the suit to your size, choose your fabric options, select your

pockets and features and most importantly colour.

My

suit of choice for bad weather and expedition paddling is the Kokatat

Expedition Suit. This suit has it all. Pockets, socks, durable exterior

and a hood. Kokatat is also the first company to allow online

personalization and customization of your suit. Check out the website

and play around with the GIZMO customizer. This allows you to custom

tailor the suit to your size, choose your fabric options, select your

pockets and features and most importantly colour.